88 Year Old Rich Guy Keeps Stolen Art

Robert "Robin" Owen Lehman Jr., the legacy of slavery, American wealth, and Benin bronzes

The Lehman Brothers rings a bell for many Americans, mostly because they were one of the many investment banks who helped plunge the US into the 2008 financial crisis. I was seventeen then, and remember vividly realizing that just a few corporations could be the catalyst for my parents trying to hide the fact that their retirements were wiped out by double digits. I was about to go to college, and the floor was falling out from under me.

While the legacy investment bank founded in 1850 no longer exists, various Lehmans are still out and about doing shady things, like Robert “Robin” Owen Lehman Jr., who is the subject of this New York Times headline from two days ago. His dad, Lehman Sr., was the head of Lehman Brothers until his death in 1969, and became tremendously wealthy in the process, enough that he was able to amass an art collection populated by Old Masters and Impressionist works alike, and valued at over $50 million when he died.

To understand one man’s reason for being in a NYT headline, let’s do some digging into the Lehman family history for a bit more context.

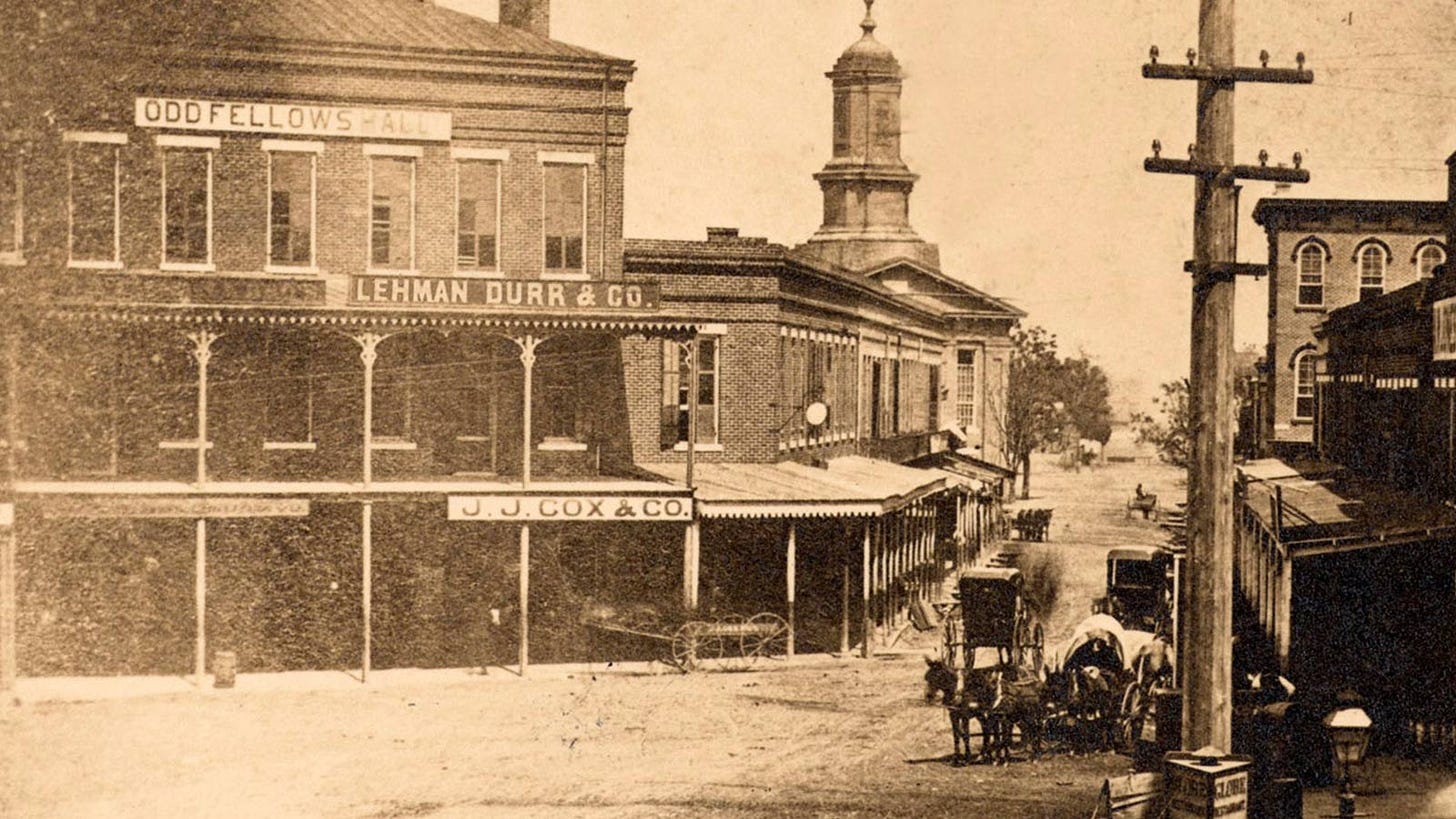

The first Lehman brothers were Jewish immigrants who came from Bavaria to Alabama in the 1840s. Henry, Mayer, and Emanuel formed a trading company that made money, lots of it, from cotton, that truly blood-stained good that relied on slave labor and colonial violence. The Lehmans owned slaves themselves, apparently assimilating well to the culture of the American South. Mayer Lehman owned seven slaves, per the 1860 Alabama census. Six years before that, “H. Lehman and Brother”, the name of the early Lehman company, bought a fourteen year old girl named Martha.

The earliest roots of the Lehman family, like many wealthy American families, are in immensely profitable violence.

Owning slaves themselves, making money via slave-produced goods, and after the Civil War, moving operations to New York, where they were significant and important members of both the New York Cotton Exchange and the Coffee, Sugar and Cocoa Exchange; it’s a bloody, slippery trail the whole way. Cotton, coffee, sugar, and cocoa were produced largely by slave or poverty-wage labor, often in colonized parts of the world like Brazil and the Gold Coast. This wasn’t a hidden reality, even back then - it was part of how mansions were built, global educations paid for, art collected.

To this day, these commodities are still harvested and produced with child and slave labor in these parts of the world, and still help international corporations make enormous amounts of cash. It was estimated in 2017 that over two million children in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire were still employed in the cocoa industry, and in 2021 companies such as Nestle and Hershey were charged with partaking in slave labor by citizens of Mali. In the state of Minas Gerais in Brazil, child and slave labor still produces coffee for Starbucks (another reason to boycott them besides their union busting).

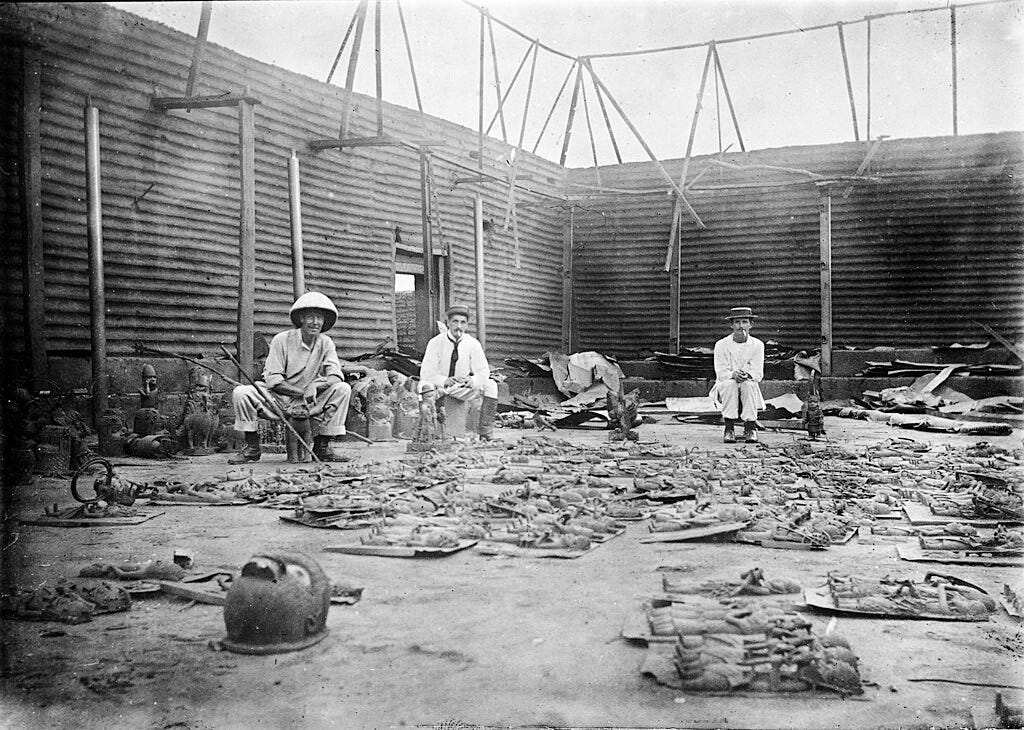

In 1897, several thousand bronzes from Benin were stolen by the British from the royal palace during the Benin Expedition. This “expedition” was a calculated, intimidating show of force meant to terrorize and stop Benin’s colonized people from fighting back against British exploitation. It’s a seemingly inherent trait of the British empire to steal shit left and right, so whether they were there to intimidate and purposefully steal, or whether the theft in the royal palace was a secondary “bonus” is somewhat irrelevant. Thousands of bronzes, made centuries before in Benin by incredibly skilled craftsman, were quickly swiped, mere raindrops in the torrential storm of countless objects stolen by the British Empire over the centuries. (It is almost unfathomable how big the British appetite for looted objects was, I really don’t think we could properly ever calculate how many things they’ve pilfered from people all over the globe.)

Once these bronzes, mostly made between the 13th and 18th century, disappeared from Benin, they re-appeared all over Britain, Europe, and America, in both museum and private collections. The fact that they came from exoticized and colonized lands, and from people not necessarily seen as fully human, made the Benin bronzes into marvels of curiosity while simultaneously lessening the crime of their theft. As the decades passed, held behind heavy wooden doors and in gilded halls, the bronzes gained legitimacy as part of these collections.

Once Nigeria fought its way out of the confines of British colonial rule in 1960, it began to ask for the bronzes to be returned. The Nigerian government has, since then, pushed for these bronzes to be returned and rallied many museums and government officials behind them into organized groups to discuss such repatriation, like the Benin Dialogue Group. Much like Greece’s Elgin Marbles (named after the aristocratic ass Thomas Bruce of Elgin, who stole them in the early 1800s), the Benin bronzes have become a test case both culturally and legally in changing how we see looting and repatriation, and how museums and governments treat repatriation cases.

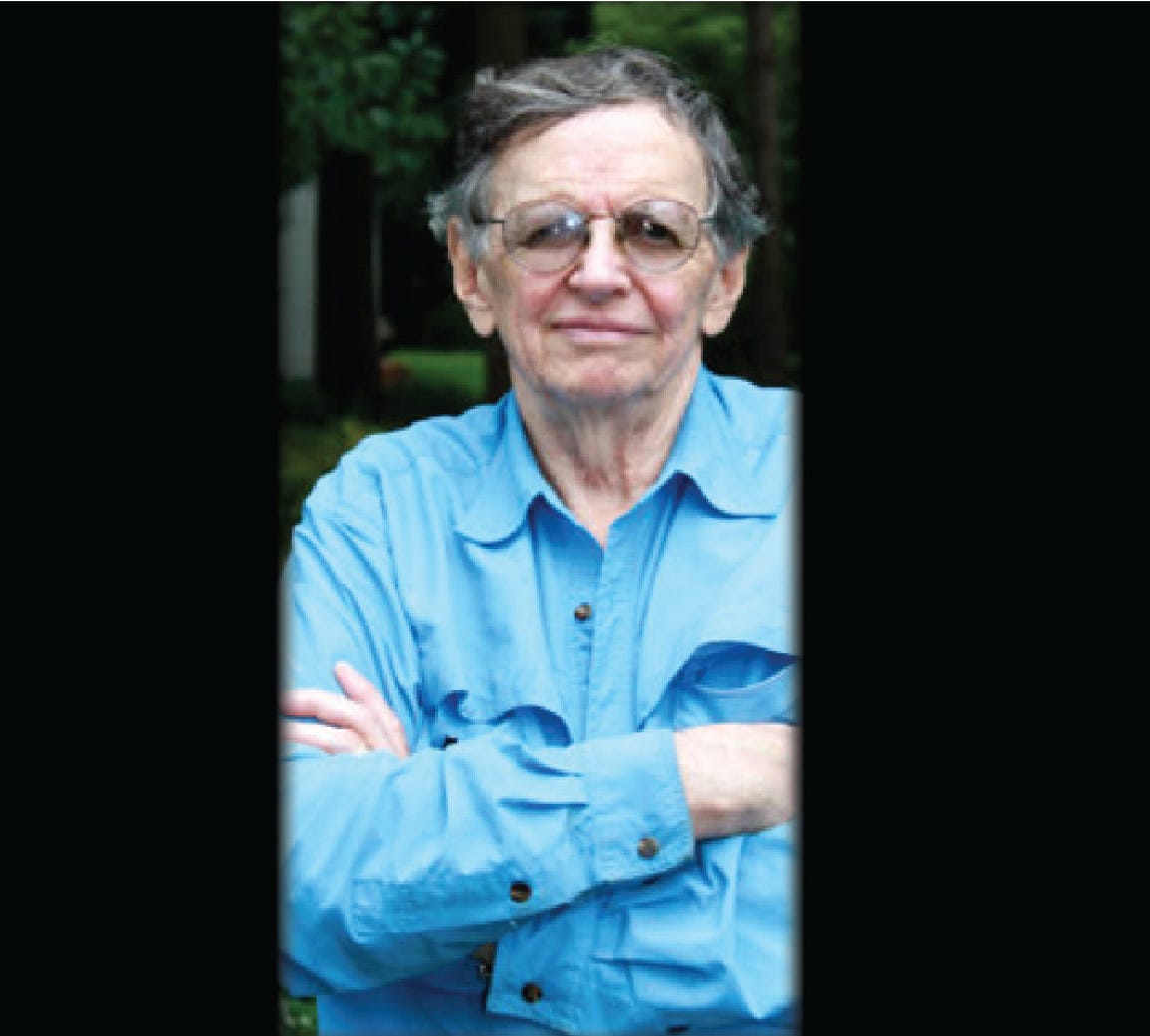

This is where Robert “Robin” Owen Lehman Jr. comes in. Born in 1936, the 88 year old scion owes the wealth that has enabled him to build his (at least partially unethical) art collection to the violent roots of his ancestors, the same people who bought fourteen year old slave children and raked in massive amounts of money from partaking in coffee, cocoa, and sugar trading and banking.

Ironically, Lehman Jr. is an artist himself, making his name as an Academy Award winning documentary filmmaker, and a skilled craftsman in his own right. One of his awards was for the 1976 documentary, The End of the Game, about the need for conservation efforts in Africa. He can have sympathy for animals, and for some aspects of the plight of the many post-colonial nations on the African continent, which he must traveled around extensively to make this documentary, but ask the guy to give up 30 Benin bronzes, from an African nation, from what is probably a tiny portion of his ill-begotten dragon’s hoard? There, the line gets drawn.

It is in 2012 that the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston accepted a long-term loan that would eventually have them owning 34 Benin bronzes from Lehman Jr. permanently. However, talks between representatives from Benin’s ruler, the oba, the MFA, and Lehman Jr. broke down literally days ago, to the point that he reversed his promised gift and has taken back his Benin bronzes, lest they go home.

Per the MFA’s website about Robert “Robin” Lehman Jr.,

The Lehman collection was formed in the 1970s and 1980s. It includes many pieces from the collection of General Augustus Fox Lane Pitt-Rivers, an avid British collector of African art and ethnographica at the turn of the 20th century.

Augustus Pitt Rivers “collected” tens of thousands of objects from around the world in the 19th century, which means he bought them from other parties, many of whom almost definitely “collected” these items under not ideal circumstances. If this is the basis of the Lehman collection, it’s as ethically wobbly as Jell-O. There is not enough time in the world to delve into the questionable, predatory strategies employed by various brokers of ethnographic and artistic goods to the many, many, many deep pocketed collectors that abounded in the 19th and early 20th century.

Lehman Jr. is far closer to the grave than anywhere else, and yet dropped out of talks with the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Nigerian government to repatriate the stolen Benin bronzes he “owns”. Instead, he has clearly decided he’d rather die with these stolen goods, and believes in the delusion that he can apparently take them with him to whatever afterlife. We shouldn’t be surprised - he vehemently fought against repatriating an Egon Schiele painting, “Portrait of the Artist’s Wife”, back to the heirs of Holocaust victims. All the money in the world can’t buy you class, and it can’t buy you morals (aren’t we living through the best showcasing of that right now?), but it’s still immensely frustrating that it can be up to one wealthy man to muck up years of repatriation efforts and stop the rightful return of such important objects.

The Benin bronzes belong back in what is now the Edo State in Nigeria. They belong home. There, they are properly nestled in context, showcasing the resource-rich kingdom of Benin that had the technology and artisans to make so many gorgeous objects. There, they are full of meaning, of life, and of soul. In Lehman Jr’s sterile, greedy grip, they are empty in comparison. They will, someday, find their way home - the tide is slowly turning, and the wave of conversation and action around repatriation is swelling. There are other Benin bronzes that have gone home, courtesy of other museums, and kudos to the MFA in Boston for being active participants in repatriation efforts.

There is no neat ending here, no nice bow to wrap this reality up in. Lehman Jr. is not alone in ensuring that he holds tight to stolen art and artifacts, but the fact that he is almost 90 years old and still refusing to loosen his grasp is pretty damn disgusting. This is just another chapter in the saga of getting things home, where they belong, and again, there is hope everywhere as indigenous peoples, governments, and other organizations band together to make signifiant changes in our collecting and retaining habits. Thanks for reading.

Really interesting, thanks for sharing your knowledge. Xo