Back in Montana

Snow geese, Northern saw-whet owls, and home.

Leaving Calgary was an exercise in Hell.

We were supposed to leave Tuesday, but a big snow storm rolled in last Monday early in the morning, and we woke up on the big day of packing and moving to lots and lots of snow, and a massive drop in temperatures. We managed to get a decent amount of our possessions in the U-Haul (which had a very chic goshawk on both sides, mouth open), but watching my husband literally dolly furniture up the ramp over ice and snow was awful. I was just waiting for one of us to lose a tooth or our sanity. My husband was one for a time during Covid, and it’s a hellish job that involved fourteen hour days, but his past labors keep paying dividends in that he knows how to stage everything, use those foul grey U-Haul blankets, tape, and sheer will to get an entire two bedroom apartment of our crap into a truck in as painless (but still wrenching) manner as possible.

Wednesday at ten AM, we finally pulled away from the regal red brick building that housed us the last two years. Our apartment echoed, our backs ached, and we were only partially done with the marathon ahead. A seven hour drive (if we were lucky) awaited us, and road conditions were unclear. Luckily, the roads were only sketchy for the first hour or so. I took over in the bustling metropolis of Nanton, Alberta and drove us all the way to Great Falls. The route, through Fort Macleod and Lethbridge, is not exactly gorgeous, and it literally stinks for a good portion of the way thanks to the plentiful feed lots that dot the landscape, but at this point the route means one thing: going back to Montana. For that reason, it is always beautiful to me.

Before we got to the border, a massive flock of snow geese, flying lower than I’d ever seen, passed over us. Their tenacity and hardiness is astounding, and I was briefly enraptured by the sight and sound of them heading resolutely south, honking the whole way, almost supernatural in their mass unquestioning adherence to this pattern. Overhead, an ancient ritual was taking place. I felt wonderfully small and excited - we were all going to Montana, and I felt like I had the best escorts and good luck signs in the world.

At the border, we had to get out of the U-Haul. Not for it to be searched, but for my husband’s I-94 tourist visa to be renewed. The border officer inside was friendly but asked lots of questions, obviously testing us and seeing if we had any reason to be stopped for longer. We’ve been together for a decade and have zero to hide (I didn’t even try to smuggle in any plants this time), and we were allowed on our way quickly. Later that night, home in Helena, I slept with the window cracked.

Sure enough, thousands of snow geese were still trekking on, even in the pitch dark. Their honking floated through the ice cold evening, through the window, and I laid there under three blankets, safe and happy, and cried a little for the relief and joy of being home and blessed by the presence of these creatures. I pictured their strong, exhausted little bodies, the sheer stamina they have to have to make these journeys, and thought about what they’d been through thus far on their route down the Pacific Flyway. In Montana, hunters can take up to twenty snow geese per day from October 4 to January 16 if using a shotgun, and can bag up to sixty snow geese per hunting season. Imagine being on your bi-annual commute, something so engrained in you and every ancestor you’ve had it’s a magnetic, unavoidable pull, and finding yourself confronting death aggressively and daily.1 It made the inconvenience of moving and the labor involved seem paltry.

Accidentally migrating with the geese was a wonderful coincidence. I haven’t heard or seen them since that night. Many of them are by now hundreds of miles south, and I wish them the best. This was not the last chance encounter with birds that week.

A few days later, my mom’s neighbor called frantically, asking what to do about an owl that had collided with her window. Oh no, I thought, and grabbed my sister, who spent years volunteering at a raptor center and knew more than anybody else how to handle such clawed and beaked and flighted creatures. The neighbor sent us a photo of the owl, a Northern saw-whet owl barely bigger a softball.

“Watch out,” my sister warned, “They’ll take your eyes out in a heartbeat.”

She then proceeded to tell us about their grip strength and speed, and how a fellow volunteer had part of their eye and the fragile skin underneath their eye cavity quickly eviscerated by such a wee beast. Raptors are efficient, lightning-quick death machines, even tiny ones. With the heaviest gloves we could find, (welding ones are preferable but we had none), we told the neighbors to get a kennel ready as well as towels. If the owl needed to be taken to the wildlife center in town, it would be best for it to be transported in a dark, towel-draped space so that it could calm down and not hurt itself.

Our neighbors let us in to their house so we could access their backyard, and they were obviously fascinated with what was about to happen. The little owl had perched himself up on a table outside. Both pupils were the same size, and both wings were tucked in neatly - good signs that he was mobile and hopefully okay. My sister said that she would go outside, that the owl would likely startle immediately, and she’d call me, gloves on and kennel ready, if needed.

I watched through the back door, observing this wonderfully small, seemingly cute little predator fluff itself up and settle. It turned its head all around - which owls can do up to 270 degrees one way - and I thought about how its little vertebrae, which are many more than ours, allow it to do so. This little owl could probably hear us inside discussing what to do, with its asymmetrical ears allowing it to accurately pinpoint exactly where sound is coming from. How strange it looked, in its dark browns and bits of black and cream and wonderfully clever little circles of feathers that create discs around its eyes. It was a perfectly engineered raptor, created to hide in dense trees and grab small mammals from the ground, built to sense the tiniest movements of paws and fur, to be able to laser-focus and pounce, and owls like these are rarely seen because they are so small, nocturnal, and camouflaged. I felt bad that it was out there in the open, on metal and plastic and after colliding with a window when it should have been perched confidently on a tree branch. It looked so small and vulnerable.

Until, that is, when my sister took her first step outside, gloves on.

The owl saw her and instantly exploded from the table with a speed I didn’t think possible. Its small wings moved rapidly, and it darted up and out of the big outdoor tent it had hidden in, up and up into the tall, dying pine tree in my mother’s yard, instantly out of sight. I was so glad - it was healthy enough to do so, and that meant that no rescue, no kennel, no towels, no trip to the wildlife center was needed. My sister played a saw-whet owl call to see if it would answer back, but it stayed silent, an instant ghost. If it weren’t for the indentation in the snow where it had landed, this owl could have been a figment of all our imaginations.2

And so, my first few days home were ones wrapped up in remembrance of where I live is a wild place. As I prepare to head to another wild place in another hemisphere, it feels pretty damn special to be reminded of how many neighbors, often unseen, I share this place with. Soon, I’ll have armadillos, coatis, all kinds of hummingbirds and parrots, siriemas, and other critters living around me - but I will definitely miss my Montana critters.

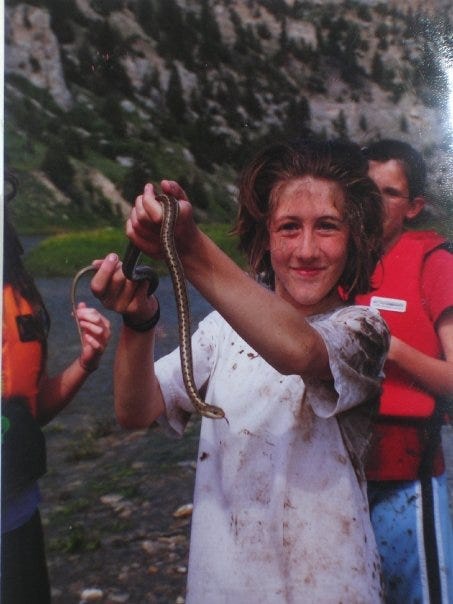

Obviously leaving you with the photo that speaks to who I truly am and always will be. Honest to goodness maybe it’s time to go back to school and become a herpetologist - I yearn for the slimy and the slithery.

Snow geese populations have rebounded so effectively from their lows in the early 1900s that they now damage their own habitats and negatively impact other animals as well. Hunting is an effective way to help control populations while filling freezers, but I am still in awe of the tenacity of almost all migrating birds, whether or not they are an ecological scourge. (I mean, we humans don’t have a leg to stand on, do we?)

For the love of all that is wonderful, please get decals or find other ways to keep birds from striking your windows. Also, keep cats inside. Wild birds die en masse thanks to cats and window strikes. There are so many easy things we can all do to help keep our non-human neighbors safe.