It’s 2012 and we’re going to breakfast together. It’s cash only. You can’t order anything off-menu unless you want to be laughed out of the county. The heating in the building is sporadic at best, so best wear a coat. And yes, there is a toilet outside the front door. Don’t touch the screen door - it might finally fall off it’s hinges.

We are going to the Bozeman of not-long-ago, but it’s a time that for me feels so far. Cactus Records was still on Main Street, where you could buy cheap tickets to see shows at the Filling Station, and rent was affordable (I paid $325 for a room in a big apartment). This Bozeman didn’t have multi-national yoga clothing stores competing for space on Main Street or Audis zooming everywhere or Yellowstone cosplayers filling up The Crystal. The Bacchus pub was still funky and cheap rather than sterile, and you could get an oven-baked bowl of mac and cheese for $5 (I know because I was very poor and this was my go-to). Sure, there were rich folks buying up land in Gallatin Gateway already, building “lodges” with heated floors (to me this is the epitome of luxury), but by and large it still felt like a college town. John Mayer hadn’t moved there yet, that insufferable prick.

We’re driving north of town down Rouse, then we’ll turn right down a dirt road. We end up in an unpaved parking lot outside a red building that looks technically more like a shed. This is the Stockyard Cafe/Calfe, and it’s a legendary spot for peach crisp, fluffy scrambled eggs, and lots of hot coffee, as much as you can stomach. It’s rough around the edges and everybody likes it that way - if you want something nicer, you can hop on the wait list at the Nova Cafe downtown.

For me, this was a place where only good things happened. The Stockyard Cafe/Calfe conjured up solely positivity and joy and communal appreciation. Chelsea, Julia, Harlan and I went there as often as possible, and I regularly photographed our gatherings. These mornings were sacred. Everything, from the rickety building to the funky plates, sang of character. I was in my “Americana diner photography” phase, and while I do not think that this counts as a diner, it was certainly a place worth photographing.

I’m taking you there in 2012 because it closed in 2017. By then, I was living in Missoula, and I hadn’t eaten in that hallowed hall since 2014. There are places worth grieving for that leave big holes in our hearts and our towns. The Stockyard is one of them. It was a special, cheap, hardy place that spoke to a community and what it still was and wanted to keep being. The Stockyard wasn’t posh. It wasn’t efficient. It wasn’t over-priced or all about aesthetics. It was a genuinely bonkers restaurant that ran at it’s own pace next to the yard where cattle auctions used to happen before all that moved to Three Forks in the early 2000s.

In the flattening and same-ness of everything, where you can be in Bozeman, Montana or Toronto, Ontario and go to restaurants and coffee shops and live in sterile buildings that all look and act the same, the Stockyard stands strong in my memory as the kind of space that lured people in and hooked them firmly by the heartstrings. The first time I went I was taken there by Julia. I don’t know how she found out about it, but it felt like the kind of place you had to be invited to. A lot of us didn’t have smartphones then, and finding a place to eat on Google wasn’t a thing. There were still hidden spots that you wouldn’t know about unless you were invited or taken there, because they weren’t obvious or easy to find. Literally every other breakfast place I loved at that point was on Main Street - the Western Cafe, Nova Cafe, the Cat Eye.

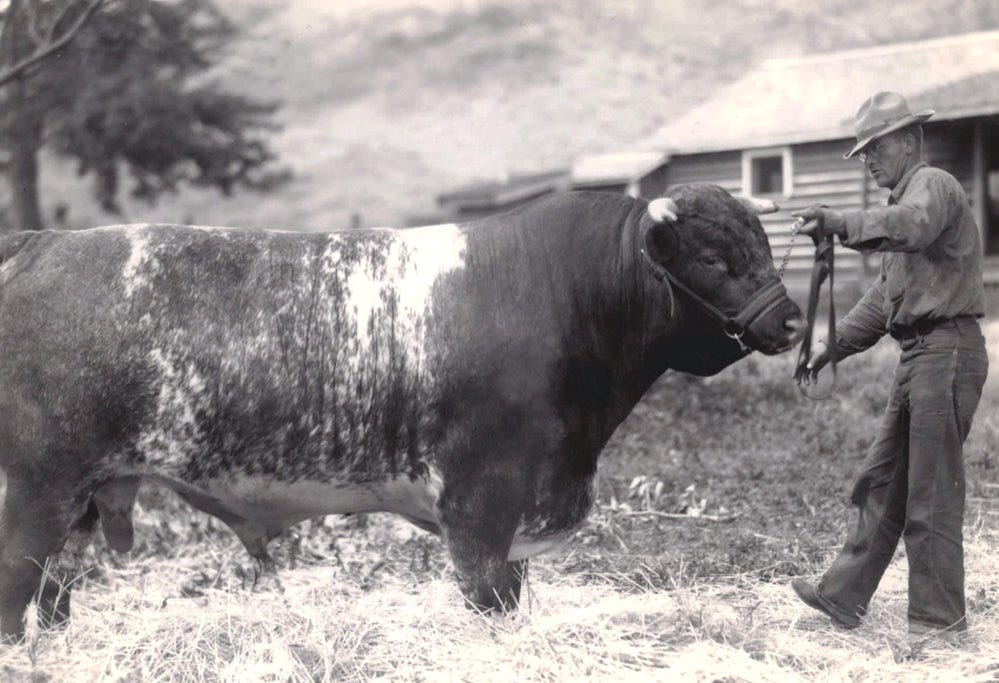

The Stockyard was constructed in 1938 as part of the Gallatin Valley Auction Yards. No wonder by the time I was there in college having breakfast the building felt like it was going to collapse around us! And yet, it was a neat reminder for a Helena kid about different legacies of different parts of the state. I’m from the mining town that became the capital, and now I was in a town that had a college where you could study the dairy industry. Big boys like this champion bull (photo from 1936) were likely auctioned off at the cattle yard, and I can only imagine people milling about, drinking coffee, with their brochures and handbooks listing what kind of cattle were for sale, where they came from, etc.

Funnily enough, I’d never actually tried to find the history of this place until the last few years - and it is tragically sparse online! Nothing on the Montana Memory portal kept by the Historical Society, nothing on my usual slate of online archives about the North American West. Nobody has photographs of the building much before the 2000s. I can’t find a lot about the auction yard either, although there are some horribly digitized images on the MSU website, of men crowded around metal gates watching cattle.

What I can fill you in on is this: the Stockyard Cafe was one of the last places that marked Bozeman, the actual town, as a living, breathing cow town. When the auction yard moved to Three Forks in 2005, that was the death knell for the actual ranching industry having a place in Bozeman proper, but the Stockyard was still hanging on and poking us in the ribs, reminding us that the empty auction yard just next to the cafe was actually quite the place.

The whole area once emanated smells of manure and hay and warm fur and probably cigarettes. The bellowing and groaning of the cows, waiting in pens or being showcased in the main rings, would echo all through the yard. If it wasn’t summer, frost would be coming out of bull’s and men’s mouths alike. People would be shrugging inside their warm coats. Impatient or stubborn animals would require prodding and poking. Folks from Belgrade, Livingston, and Three Forks would all be coming in, bad weather or no.

Montana still holds strong to it’s agricultural ties. A lot of folks pride themselves on being in a state where we grow and raise a lot of our own food, from wheat to cattle. I worked at a brewery where the brewer made beer with wheat from his family’s farm near Townsend. However, that agricultural legacy has been changing, and quickly. Montana lost 1,600,000 acres of farmland from 2012 to 2017, often because aging farmers and ranchers can’t find younger folks who can afford the high prices of land.1 To get market value for their ranches, families often sell to private developers or rich boors looking to live out their Manifest Destiny myth. (The Running Elk Ranch outside Bozeman was for sale for $80 million dollars this summer, a new record.) Climate change, especially drought, has impacted farms and ranches alike, and a monopoly of meatpacking plants by four large corporations has left ranchers getting record low profits for record high beef prices.

On all sides, agricultural families are having a hard time. A long time ago I worked at a callcenter for the USDA, contacting farmers to see how much grain they’d grown that year, if they were selling, if they were storing it. More than once I got an earful from farmer’s wives about how their husbands couldn’t come to the phone. They were working a typical twelve hour work day and for next to nothing.

What does this have to do with a little run-down 1930s building that housed a precious breakfast spot?

The loss of real memories and perspectives of real folks who worked hard - not shellacked, 2-D nonsense about cowboys that makes people in brand new boots strut down the street. While Bozeman has allowed itself to become cloaked in an expensive cape of hyper-masculine, individualistic white man Western myths, and rife with pricey steak houses, it’s all a gilding that comes off if you barely scratch it. But, you have to scratch it. You have to find a reason to agitate, to poke, to get beyond the surface and see what’s real.

If you’re one of the many folks in Bozeman living hand to mouth and you can’t really picture yourself strutting in brand new jeans downtown out to spend some cash, maybe you want to poke. (I don’t ever assume that people know the history of where they live. We don’t value the humanities the way we should, which always bites us in the ass one way or another, but I can’t begrudge folks who weren’t given any real reasons to care about the past to know it when we’ve all got to worship at the cursed alter of the Almighty Dollar before we can have space to feel and think.)

The Stockyard was surrounded by smells, sounds, and the lived realities of thousands of people and animals for decades, and pulling in that parking lot, which was dirt or mud depending on the time of year, you could be transported back a few decades without a thought, to a real place that was an integral part of people’s lives. Being able to easily feel connected to and wanting to understand the context, the past, the whys and hows of where you live now, is important. It helps give you grounding for what’s happening now, and it gives you ballast to imagine the future, and hopefully you can imagine a future with you in it.

Community requires curiosity and questions and engagement, and I think having accessible, interesting windows to the past of any kind - a cool old mansion on your block, a corner bar from the 1930s, a cheap diner that’s in a questionably heated shed - makes that simpler. When you appreciate and build relationships with the old bits, the weird bits, the anachronistic bits that hopefully make up the place you live in, it’s easier to care more about the future of that place as well, because you have a connection with the things that make a town interesting or worthwhile. The Stockyard was not just a reminder that Bozeman was a cow town, it was a place that allowed people to feel welcome, to be part of something a bit funky. It made us college kids, who could easily live insulated lives outside of the community, care a little bit more. Possibly even more important, we could afford to be there.

There’s also a gaping hole left in our communities when we lose affordable local spaces to gather together, which are becoming fewer and fewer no matter where you live. The ability to gather somewhere that’s not your house, and isn’t a chain, without shelling out forty dollars for a meal or drinks is essential; I regularly lurked at cheap places getting the most affordable thing on the menu, sometimes just ordering tea so I could sit with my friends. I worked in the college cafeteria taking out the trash and scrubbing dishes, and with those wages I could still afford to come get peach crisp at the Stockyard and more than enough hot coffee, seated with my friends.

Bless the Stockyard for being a wonderful bright spot in my three years in Bozeman.

I miss the warm brown Formica counter, the sizzle of the wood-fired griddle just a few feet away, the hum of the fan above, the quick movements of the severs and cooks who whirled around the cramped space, plucking orders from customers and leaving oval-shaped plates of food. I miss the culture, the rules that everybody respectfully observed, because we all knew that this was a special place that had fully earned it’s own customs and whims. When you were done eating, you didn’t dilly-dally - there were always folks waiting to saddle up to the counter and have a warm meal. The plush textures of dozens of winter coats much of the year in the low-ceilinged space made everybody look like fluffy birds crowded in a nest, and if you knocked elbows or touched knees, nobody made a fuss. I think that we all knew that we were lucky to be there.

The Stockyard sits on land that will eventually be developed. Of course, development is not all bad - Bozeman is growing and affordable housing needs to be built, and NIMBYs are making that awfully hard to do in town. The area that the Stockyard was in is a historic area that also hosts the Story Mill, and it will be a beautiful place to live and work, but I’m not holding my breath that people who make local wages will be living there. It’s hard not to feel resentful, watching whole swaths of my mother state become inundated with out of state cash, luxury Mercedes camper vans, and AirBnbs, but ruminating won’t actually solve those problems. (Legislation will! Tenant unions can help! Make it so that the many, many landlords in the state legislature are made asses of when they center their own profits over their constituents!) I am hopeful for our upcoming legislation session in the spring that, who knows, might yield some hope!

In any case, I count myself lucky to have been young and well-fed by the wonderful “calfe” that was the Stockyard. May we all have places like these that shine on in our hearts, that gave us shelter and nourishment in more ways than one.

Until next time, be well, be kind, and share a warm meal with somebody you love.

From “Aging Farmers, Vanishing Farmland,” Earth Island Journal.

This was a good read and forgive me for focusing on a typo… But maybe soon it will be possible to attend a college somewhere and study the diary industry.